The reason I had a hard time back then was not a lack of good documentation or badly implemented software. No, quite the opposite. It was the vast amount of different choices I select. Which program to use for recording, which underlying sound server, should I use a real-time kernel or not… And with every choice I made several new options popped up. Don’t get me wrong, this is the true power of the Linux system and enables advanced users to surpass everything they possible could accomplish with Windows or Mac. But back then I was (even more of) a newbie and I simply failed to get the bigger picture of the Linux sound system. As a result, I was not able to trace back occurring errors and thus could not properly search for a solution online.

That’s why I want to share my experience and try to give you the bigger picture of the Linux sound system and its interplay with the recording software. I will not provide you with detailed information about how to use specific software. This you can find in many places online, foremost at the official web page of the software. This post concentrates more on the peculiarities of Linux’ take on audio and the differences to other operating systems. In addition I will point out some nice applications to start recording with and hook you up with a number of links for further reading so you can pick your own flavor of the Linux audio experience.

For whom I write these lines?

I intend to write this post for both musicians thinking about using free and open-source tools to handle their music and for Linux users curious about recording some audio.

I will divide this topic in two separate posts: In the this first post I will provide a simple introduction into the Linux sound system, but concentrate more on its overall character and on programs to use during recording. So if you just want to record some music and are not that interested into the underlying peculiarities of the Linux sound system, here you will find what you are looking for.

If you experience some problems with you setup or want to learn more about what’s going on under the hood, check out the second post of this topic. In there I will shed some light on how the ALSA part of the Linux kernel is handling your sound cards and how the interplay and the configuration of the Linux sound servers PulseAudio and JACK does work.

Please note that these posts are tailored for actual audio recording. But if you want to generate some electronic sounds using MIDI instead, don’t worry. Most of the steps described in here will apply as well.

What makes Linux audio processing hard/different?

For those of you new to the Linux system you might wonder why I make such a big deal out of this topic. Can’t we just use a big program handling everything related to our recording session, a so called Digital Audio Workstation (DAW), like Cubase on Windows or Pro Tools on Mac?

Unfortunately not. Linux is just not intended to be used this way and it is very important for you to understand the actual difference to be able to harness its true power.

The Unix principle

One of the core concepts of the Unix philosophy is to

Write programs, which do one thing and do it well

This way you break down complex problems into smaller ones, each addressed by one free and open-source program (and its alternatives) and maintained by a small group of people. Those small and robust programs you can then glue together to produce a sophisticated, modular, and highly personalized workflow solving all your problems.

What sounds really nice for programming tasks or the personalization of your desktop feels quite alarming when handling audio. So there is a program handling the playback of your recorded audio, another one applying a compressor to it, and a third one being the compressor itself? And I have to glue them together manually? Well, yes and no, not necessarily.

Fortunately the handling of the effect chain is done by your recording software, relying on the underlying Linux sound server responsible for gluing the individual programs together. So by using Non DAW or Ardour with JACK or Audacity with PulseAudio you will have a DAW for handling your audio after all.

Well, then what does make the Linux system different? Two things: First, you are not restricted to your DAW anymore. You want to extract some audio from a movie and incorporate it into your music? Just connect the vlc player or another sound source in your system to your recording program. You found a neat little (jack-aware, see later) audio tool in the internet? Just integrate it into your workflow. The difference in volume between dialogs and action scenes in movies gets on your nerves? Just add a compressor between your browser/media player and your system’s sound output. The possibilities are endless.

Secondly, if some plugin (like an EQ) in your recording software crashes, do not blame the authors of your DAW. Most of the times those little plugins (like LV2, LADSPA, Calf , or TAP) are small programs themselves being maintained by a different group of people. Keep this in mind while searching for a solution online!

Multi-user system

The Linux system is intended to be used by many users at the same time. Not just the huge machines in some clusters of universities or companies, but your personal laptop with just one configured user account too. Just enter the following command into your Bash to list all available users on your system.

cat /etc/passwd

Next to your actual user and root there are many system services, like lp for printing or lightdm for handling your graphical desktop, having an user account by themselves. This is done by Linux in order to strength the security of your system. Even when an intruder is able to obtain access to one of your system’s services, the person would end up in an account having very limited privileges. For all those different users to work together on a single machine, the Linux kernel provides a scheduling system that allows all users to access the system’s resources, the CPU, and all the additional hardware on more or less equal terms.

But here we run into problems when dealing with audio on a Linux system: accessing your sound card and writing the input to disk by your DAW does have in principle the same priority as your Thunderbird while checking your mail. The more users/programs/services want to use your CPU, the less time every one has to perform its task. Thus the latency (the time your signal needs traveling from the input of your sound card to the speakers) in Linux systems is quite high.

In order to reduce the latency one can use a Linux kernel tailored for real-time usage (those with an -rt- in their name) or allow the recording software to put a higher load on the CPU by changing the configuration of the underlying Linux sound server. Both options are not at all recommended for people new to the Linux system. You haven’t compiled your own Linux kernel yet? Then do not consider doing so just to improve your latency!

Four years ago I wanted to get Ardour and JACK running on low latency. But on heavy load the setup created some kernel panic (as I know in hindsight) and my system froze whenever I something was going on in the background or my Ardour-files were getting to large. I tried to fix it. But I failed and it was a massive waste of time. Better don’t go along this direction.

Don’t get me wrong. I encourage you to try some low latency settings. But when you experience severe problems you can not really reproduce, do it as Scar advised in the lion king: run away and never return! (unless you become a Linux-pro by then)

So when you do not need a very low latency setting, don’t go for it!

Choice of recording software and sound server

Now that you are aware of the most important features and restrictions of the Linux sound system, let’s try to answer the following question: What recording software and Linux sound server fits me best?

Need for low latency

The most pressing subquestion on our way the determine the answer of the former one is: Do I need a low latency setup?

You do so whenever you want to use monitoring (listen to the recorded sound) while recording. This is for example the case when you input a clean guitar into your system, apply an amp simulation via some software, and listen to the resulting output while actually playing the guitar. Another common scenario is to play a keyboard while using not the keyboard’s sound synthesizer but a Linux based one.

In those cases you should use the JACK sound server over PulseAudio since the former has a better latency handling. Along with it I would recommend using the Non DAW (or Ardour) as recording software. Use the default settings of the sound server and check whether the latency is already low enough for you to barely hear any delay at all. If you do and you have to get to even lower latencies, you have no other choice but to apply some real-time settings for your kernel and settings.

If you have a nice amp and want to record, mix, and master your music, you are actually not in need of a low latency setting. Instead I would highly recommend you to buy an external sound card capable of monitoring on its own. Those devices split the signal into two and supply both your computer and some headphones/boxes with the original sound. Therefore, there is no need anymore to keep the latency as low as possible. I’m using this sound card and it’s doing quite a fine job. But before you get yourself a sound card, make sure it will run properly with your Linux system (list of supported devices by the alsa-project and the (German) audio for Linux page).

Degree of sophistication of your sound server

In case you don’t need a very low latency setting, you have two choices:

- Use the PulseAudio system along with Audacity, which works out of the box and is a very robust but basic system. For some quick recording and mixing this should be your system of choice. If you on the other hand do not intend to just record and mix some tracks but to build your own professional audio processing system, you will find its features too limiting.

- Use the JACK sound server with Non DAW or Ardour. This setup let’s you harness all the power of the Linux sound system but it’s also not that straight forward to set up and configure.

If you are (completely) new to Linux or want to get things done quickly, I would recommend you to use the first option. In all other cases try the second one. It needs more time to get started, but you will have more powerful tools at hand in the long run.

In the next sections I will present a number of helpful programs to be used along with those two options. This will be of course just a very sparse compilation and most of the programs will actually run with both sound servers. It’s intended to serve as a convenient starting point for the corresponding setup. For a more detailed introduction into the individual applications, please follow the corresponding links, and for more information regarding the sound server and their configuration, please see the second post related to this topic.

Recording using PulseAudio

The best thing of the PulseAudio setup is: it’s (most probably) already installed and running on your Linux system. So you basically just have to install the other programs via your packet manager and you are good to go.

Configuring PulseAudio

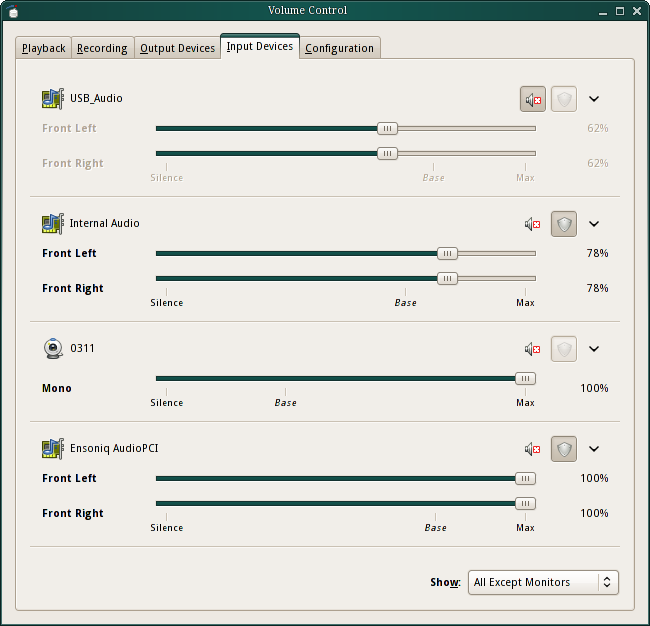

The different inputs and outputs of your sound system can best be handled using pavucontrol. But be careful! You can use this control to test your system. But do not try to select one and the same sound card (in case you have more than one) with both Pavucontrol and Audacity. They will interfere with each other and you most probably end up with no input/output signal in Audacity.

Also check out pasystray to control PulseAudio via a small icon in your status bar and paprefs if you want to use it via your local network.

Local network? That’s right, you can use PulseAudio to transmit audio signals via your network. So in principle you just have to have one computer (e.g. a Raspberry) connected to your speakers and all your other devices can stream their audio to this machine for playback. I works rather smoothly but it’s not intended to be used with wireless connections.

Audacity

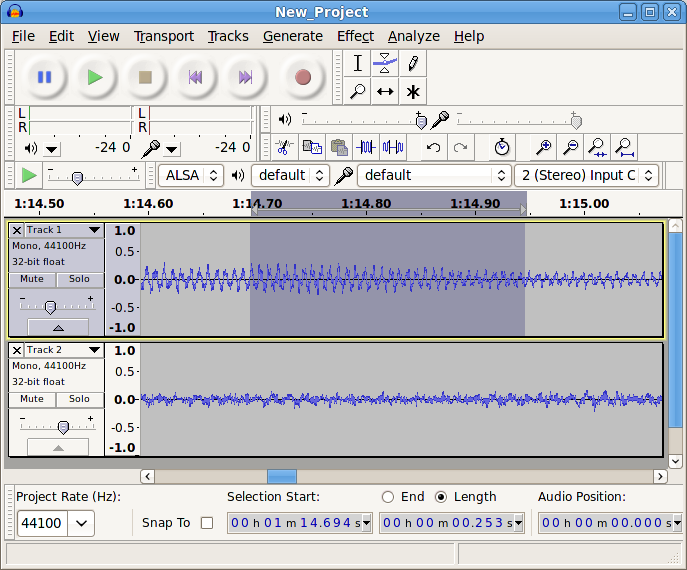

Audacity is a full-fledged recording software allowing you record audio and mix the results. It features a wiki, a detailed manual, and an active community. Check out its feature list to get a feeling of what it’s capable of.

I do like this program a lot. It’s simple, got many essential features without being overloaded, and it’s easy to use. As long as you do just basic recording and a little bit of audio manipulation, you will find everything there you need.

For a more profound audio processing I would nevertheless discourage you from using it. The reason is its invasive audio manipulation. In other words, every time you apply an effect to some selected audio the original one gets overwritten. In order to slightly change a parameter of your effect, you have to undo your changes and reapply the effect with a different setting. This gets quite cumbersome as soon as you want to mix many audio tracks in parallel.

For all of you who have tried Audacity in the past: Compared to its state when I first came into contact with it some ten years ago the application did a huge step forward. So it may be much more powerful than you actually think. Just give it a shot. ;)

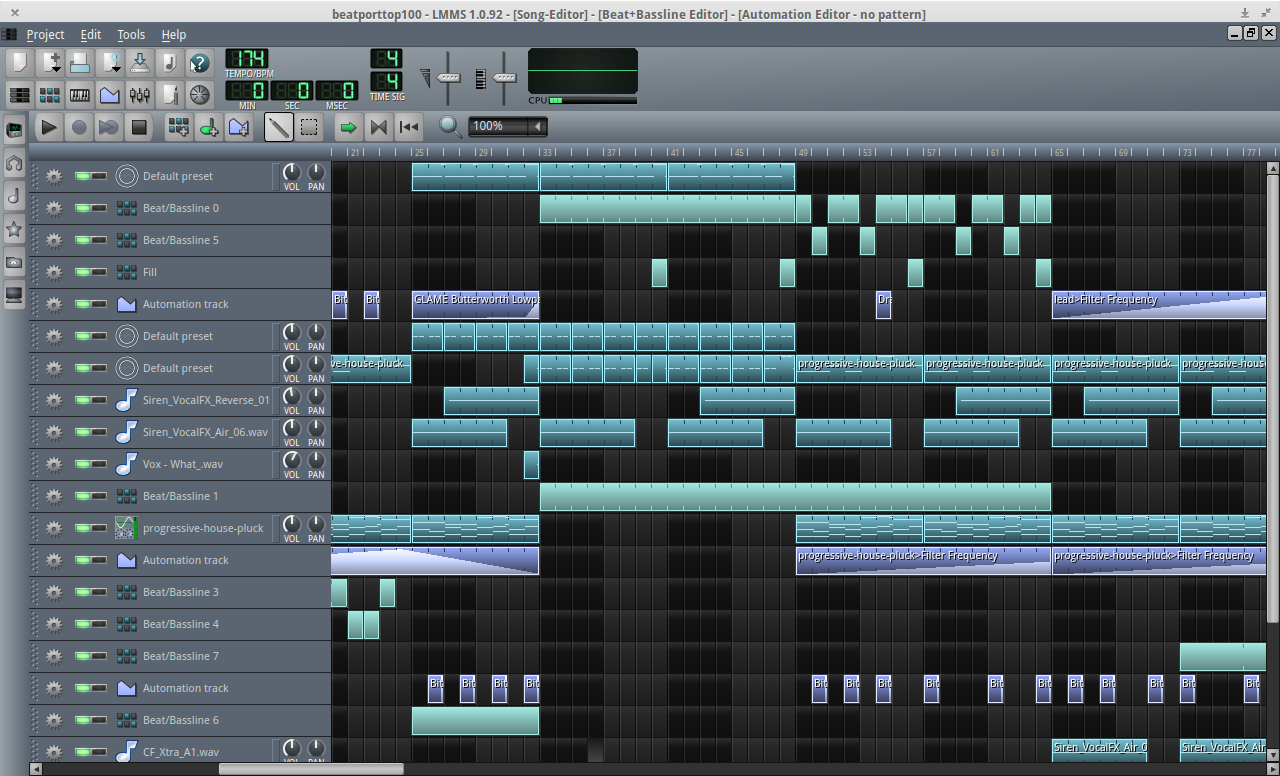

LMMS

What’s Audacity for working with sound signals (e.g. an amplified guitar) is LMMS for working with MIDI sounds. It features an extensive documentation and serves as both a MIDI sequencer (a program to write MIDI tracks) and a MIDI sound synthesizer (a program replacing a MIDI signal with a corresponding sound).

LMMS offers a great way to produce some electronic sound. If you on the other hand just intend to produce some artificial drums (and nothing more), I would recommend the use of Hydrogen instead (see later).

Recording using JACK

The configuration of JACK is not as straight forward as with PulseAudio. Fortunately you do not necessarily have to get a plain Linux distribution and set up the JACK server all by yourself. Others already did this for you and bundled the result with a ton of audio software. Thus, you find a number of different Linux distributions already tailored for audio recording and processing. If you are new to Linux, I would definitely recommend using one of those (maybe on an addition partition using Grub2).

The most widely used ones are UbuntuStudio and KXStudio. They do not just provide a preconfigured environment but also loads of resources and documentation to use them properly. Others are Audiophile Linux, AV Linux, or FedoraJam.

Worth mentioning, but quite out of context, is also RuneAudio. It intends to convert your mini computer into a high quality media server.

Configuring JACK

To handle JACK you firstly have to configure its startup and secondly to deal with all the connections between the programs.

For both steps there are a number of programs solving the task. But I would recommend QJackCtl, which can handle both of them.

To connect the output of one app with the input of another, just press the Connect button and draw a line between the two nodes by hand.

As an alternative (e.g. when you are using KXStudio) you can use Cadence and its siblings to control the JACK sound server.

Note: you have to use applications capable of communicating with JACK!

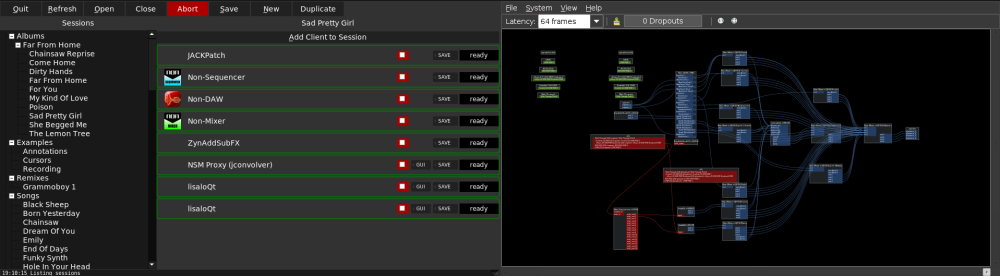

Non DAW

Instead of providing a monolithic DAW defying the Unix principle, the Non DAW consists of four stand-alone applications.

Non Timeline

For recording and editing audio.

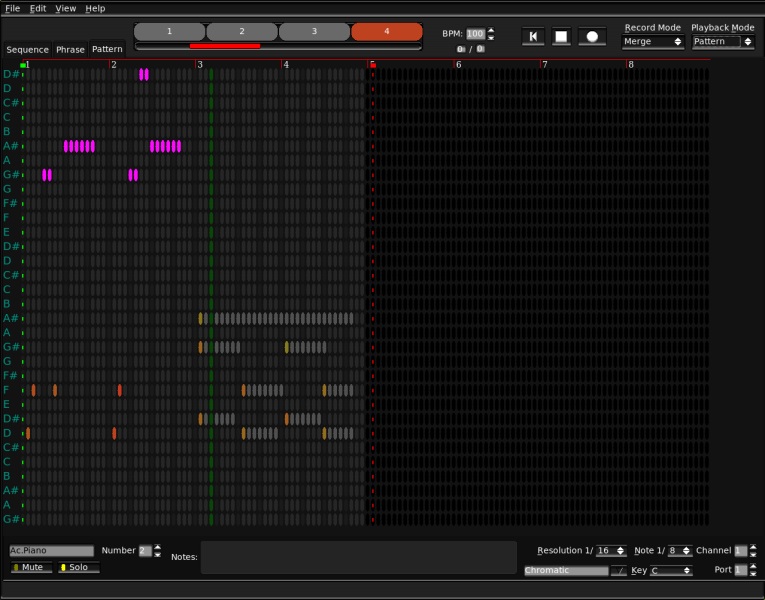

Non Sequencer

For sequencing and synthesizing MIDI sounds.

Non Mixer

For mixing different audio tracks (recorded in e.g. Non Timeline or Non Sequencer) and applying effects like LADSPA to them.

Non Session Manager

To control and restore your recording session.

You are not forced to use or even install those four applications together. You could easily use e.g. a different mixer instead of the Non one (but I would highly recommend to stick with the original one) with Non Timeline.

Since the Non suite is incredibly powerful and at the same time very slim and clearly structured as well as really fast, it is my recording application of choice. The only downside for Linux newbies may be the fact that you have to compile those applications from source. (Well, maybe they are part of the repositories of some Linux audio distributions. Don’t know)

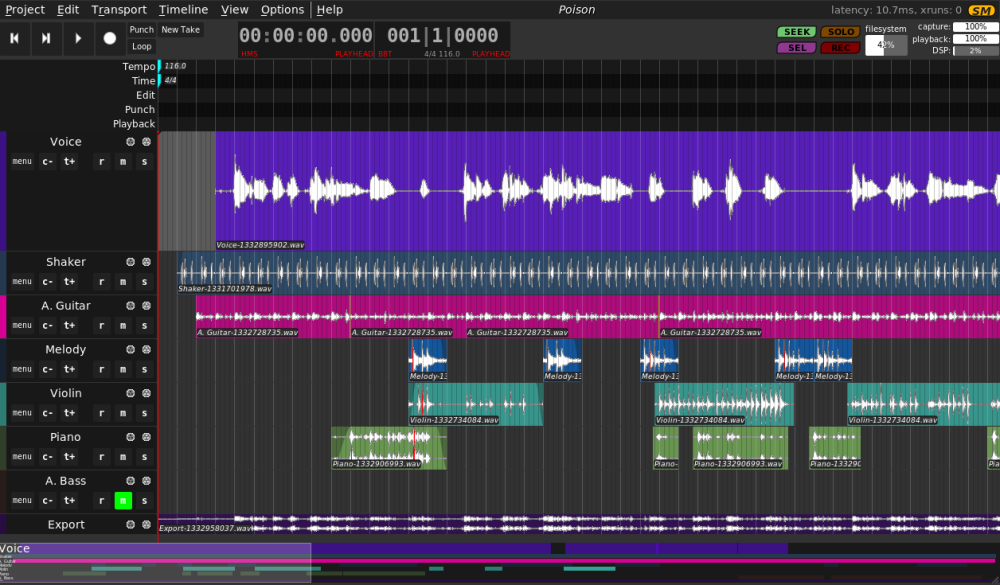

Ardour

An alternative to the Non suite is Ardour. For a JACK-based application it is quite user friendly since it takes care of starting up your JACK server and connecting all the basic inputs and outputs. On the other hand the application itself is overloaded by features and has grown more complex than necessary.

But again: If you are new to the Linux system, this might be the better entry point into the JACK-based world of audio processing.

Further applications and hints

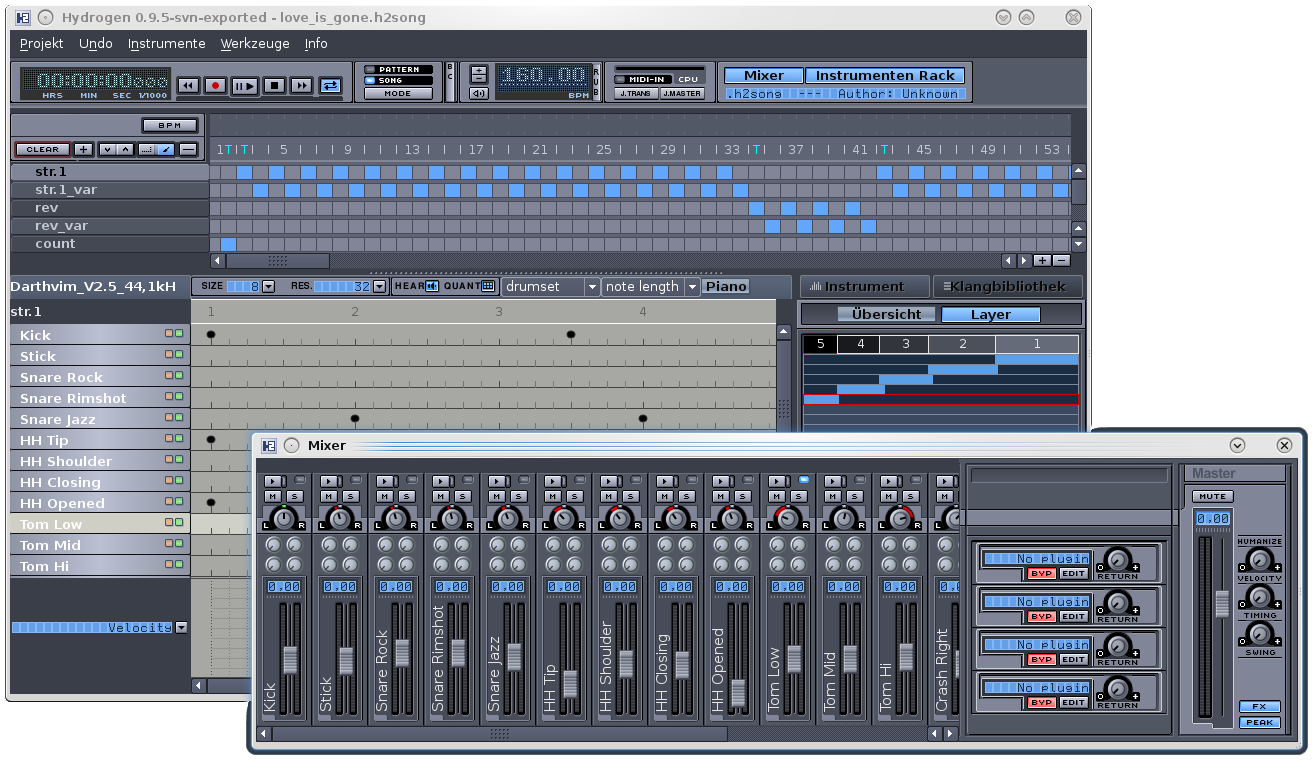

Hydrogen

Whenever you want to make some artificial drums along with your music, I would recommend the usage of Hydrogen. It serves as an application for both programming/writing your MIDI-based drum tracks and replacing the MIDI notes by synthesized drum sounds. Keep this in mind. It was strange for me in at first, but tools like EZdrummer actually do the work of two programs seamlessly: of a MIDI sequencer and a MIDI synthesizer.

Worth mentioning is also DrumGizmo due to its very interesting approach. But this program serves as a synthesizer only and you have to rely on LMMS or Hydrogen to create your MIDI drum track.

TuxGuitar

TuxGuitar is the open-source alternative to GuitarPro and an awesome way of noting down your (string-based) music.

For quite some years the project seemed to be abandoned. But luckily someone continued the development and there were two new released versions during the last year (2016). So the tux is not dying here after all. :)

Communities dedicated to Linux audio

Of course there are a number of web pages specialized in providing you with information about the Linux audio system and how to use its tools for crafting music.

- LinuxMusician and their wiki

- planet.linuxaudio.org and their main page to get in touch with new projects, resources, and software for Linux audio

- Crazy audio

- Libre Music Production

- ArchLinux wiki on how to configure a professional Linux audio system

- Audio4Linux a German web page with a nice wiki and forum

- Linux-audio.com featuring a general introduction into Linux as well as a number of links to configuration tutorials

About amp emulation

As with most commercial DAWs within Linux you also have the option of recording a clean guitar sound and emulating the effect of an amplifier using software (e.g. with Guitarix or Rakarrack). But at this point you really start to feel the difference between free and open-source software and overpriced commercial one. The artificial guitar (and drum) sounds of Linux applications are not that sophisticated.

Instead I would recommend you to get a small (preferably valve-based) amplifier and some effect pedals and record your songs via the line-in or microphone. I have a Blackstar HT-5 for all my home recordings and I enjoy it very much. One to five watt are more than enough for your living room and nothing can beat a real valve amp.

Recording tips

I won’t go into any detail regarding the actual recording procedure in here. You can find lots of recording tutorials online.

Do not restrict your search to the applications named above. Almost all tools in Cubase or Pro Tools do have an equivalent in the Linux world and with your working setup you can transfer their tips and tricks to the Linux realm in no time.

Only a few hints to wrap things up: - Tune your instrument and attach new strings - Always use a microphone instead of the line-out of your amp (for the final recording). A good sound has to travel through air at least once - Do not try to make each single instrument sound as massive as possible. In the end it’s their interplay between all of them that matters most and in mixing you end up cutting as many frequencies as you are boosting.

Further audio posts I plan to do in this blog

In the near future I intend to fulfill one of my longtime dreams: to go on a journey for the perfect sound of my music.

Being able to compose and play the music you love the most is just one side of the coin. The other is its actual sound. I want to shape the sound of my music the best way possible by just using my little guitar amp and tons of free and open-source software. And of course I also intend to write about it. :)

Just in case it takes me a while and you are already curious, I will provide you with my current curriculum for the next week(end)s/months.

After reading chapter 10 of Daniel James’ Crafting digital media for an introduction (don’t buy the whole book for this one chapter), I will read the following: 1. The first two chapters of Meinard Müller’s - Fundamentals of Music Processing to get the vocabulary of the music processing community 2. The documentation of different Linux audio plugins (LV2, LADSPA, Calf , or TAP) and decide which set of those I will use along the next parts of the journey 3. Read Izhaki - Mixing Audio to get some basic mixing skills 4. Read rest of Meinard Müller - Fundamentals of Music Processing to learn how to analyze audio. The overall goal is to be able to manipulate music in such a way it sounds as close as possible as some reference songs 5. Read Bob Katz - Mastering Audio: the art and the science to get deeper knowledge about the mastering process